Simplifying “Outlive” to Extend Your Healthspan

Don’t want to read? Then listen

Outlive is one of the few books I’ve read in the last decade that has completely reshaped my workout and diet habits. Two key reasons for this are trust and intent.

I trust Peter Attia’s insights because he’s a researcher who doesn’t shy away from changing his views when new data emerges. Unfortunately, that’s a rare quality these days, even in fields where you’d expect it the most, like physics or biology.

The intent of Outlive is to help us embrace lifelong athleticism and make sure that our final decade on this planet is full of energy. I don’t know about you, but the idea of being over 70 and still able to do pull-ups is pretty appealing.

If you’re not up for reading Outlive but still want to boost your healthspan, this post is for you. My goal here is to distill this 500-page book into a simplified blog that breaks down the actionable steps and explains why they matter.

I’m breaking this guide into three sections: Intro, Checklist, and Rationale.

- Intro: I’ll give you a brief overview of Peter Attia’s unique approach to longevity.

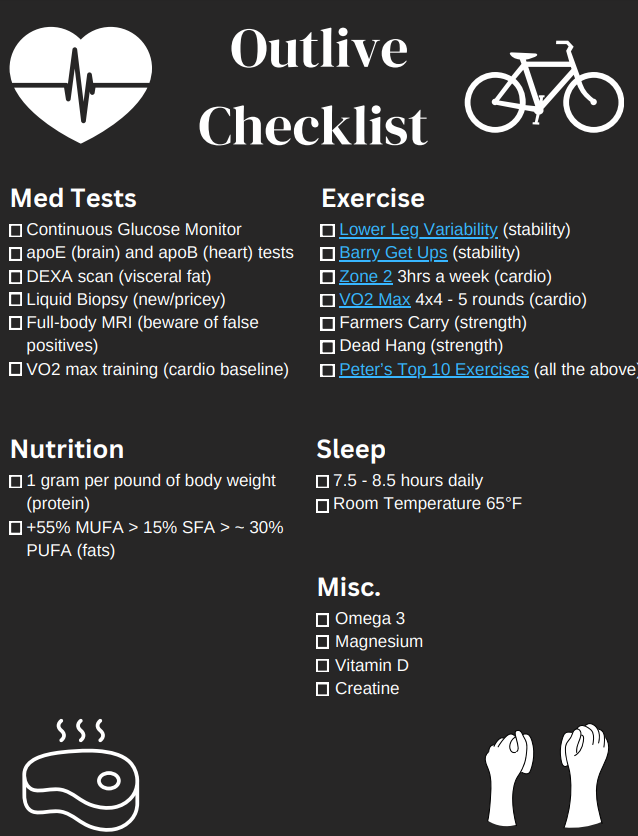

- Checklist: Below is a PDF checklist for those who aren’t too concerned about the ‘why’ but just want to jump right in.

- Rationale: We’ll run through Peter’s reasoning behind the exercises, nutrition, supplements, etc.

Let’s kick things off with the introduction…

Intro

Throughout the book, Peter consistently mentions a term he coined “Medicine 3.0”, which we can think of as a more proactive approach to health.

“The goal of this new medicine—which I call Medicine 3.0—is not to patch people up and get them out the door, removing their tumors and hoping for the best, but rather to prevent the tumors from appearing and spreading in the first place. Or to avoid that first heart attack. Or to divert someone from the path to Alzheimer’s disease. Our treatments, and our prevention and detection strategies, need to change to fit the nature of these diseases, with their long, slow prologues. (p. 29)”

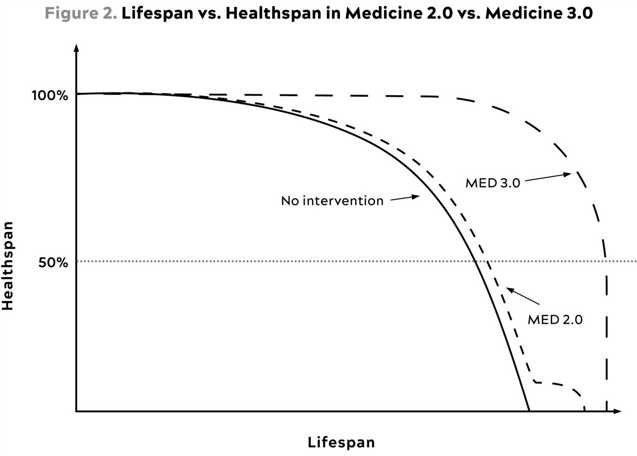

The main goal for Medicine 3.0 is simple, it is to increase our lifespan and more importantly our healthspan. The below chart provides a great visual for this and here’s a great short video explaining the idea.

When adopting the practices from Outlive our goal is to extend our healthspan as long as possible and to do this we need to delay the four primary causes of death. Or as Peter puts it…

“Living longer means delaying death from all four of the Horsemen. The Horsemen do have one powerful risk factor in common, and that is age. As you grow older, the risk grows exponentially that one or more of these diseases has begun to take hold in your body. (p. 43)”

These four diseases amount to over 80% of deaths in people over 50 who do not smoke

- Atherosclerotic disease (comprised of cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease): Simply put, the blood in our body stops flowing like it should.

- Cancer: You know what this is

- Neurodegenerative disease: Our brain starts to malfunction, with Alzheimer’s being the primary example.

- Metabolic diseases: This is a spectrum of everything from insulin resistance to fatty liver disease to type 2 diabetes. Think of it as the body’s inability to process macronutrients effectively.

Medicine 3.0 attempts to counter these four horsemen in five ways: exercise, nutrition, sleep, emotional health, and exogenous molecules (drugs, hormones, supplements). In this post (and the book) we’ll focus on exercise, nutrition, and sleep.

But first as promised, here’s the checklist if you’re not interested in the rest. 😉

Medical tests

Before jumping into different behavior changes, we’ll want to understand our current health, so the changes are tailored toward our situation.

These tests are broken into continuous and ad-hoc.

Continuous

- Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM): This helps us monitor blood glucose levels in real-time, so we can make data-driven changes on the food we’re eating. Those foods that spike our glucose we’ll want to shy away from. Peter recommends wearing a CGM for an initial ~6 months so you can understand what spikes your glucose, then afterward you can take it off (if you’d like).

- Cost: $130 – $430 per month

- DEXA scan: Peter insists that his patients get a DEXA scan annually and he’s looking for changes in their visceral fat. You only need a few pounds of visceral fat to drastically increase your chances of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

- Cost: $100 to $400

- apoB: A blood test that checks for the concentration of apoB-tagged particles. The lower the better. The ideal levels are around 20 or 30 mg/dL, which is where it would be for a child, but most people are around 90 – 120 mg/dL. Peter requests his patients take this test “regularly”, not sure what regularly means, but GPT says every 1 – 5 years.

- Cost: $30 – $100

- Mitigations: If your apoB levels are high (100+), then here are some drugs Peter uses on his patients to knock them down to ideal levels – 20 or 30 mg/dL (alongside nutrition and exercise).

- He starts with rosuvastatin (Crestor) and only pivots from that if there is some negative effect from the drug (e.g., a symptom or biomarker)

- For people who can’t tolerate statins, I like to use a newer drug, called bempedoic acid (Nexletol)

- If that doesn’t work, then he’ll use Ezetimibe (Zetia)

- Then last is Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (Vascepa)

- Colonoscopy: Peter recommends getting your first colonoscopy at age 40, then running them every 2 – 3 years depending on the results. This is much earlier than the standard recommendation of 45 or 50.

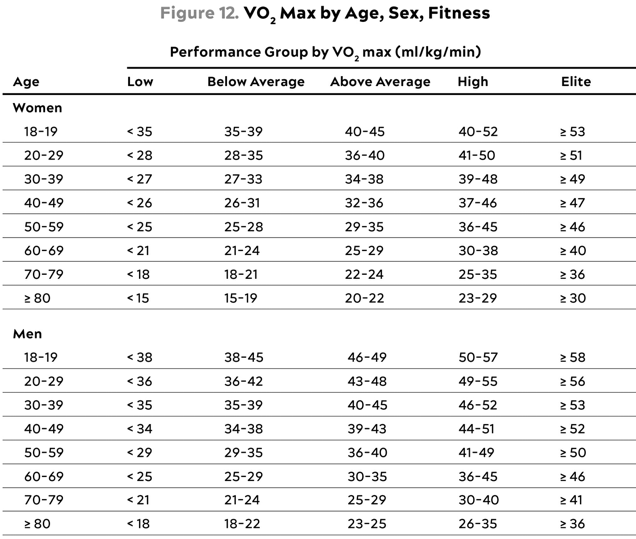

- VO2 max: It’s recommended to run an initial VO2 max test to get a baseline for your cardio. Afterward run it annually to track if you’re elite in your age range or even better, elite 2 decades behind your age group (more in the cardio section).

- Cost: $75 – $300 depending on the facility

Ad-hoc

- apoE: Genetic test that checks for the type of “e” protein pair you have, which dictates your likelihood of getting Alzheimer’s. The three variants are e2, e3, and e4. E4 is bad and if you have e4/e4, then you’re twelve times more likely to get Alzheimer’s. E3 is less bad and the most common, e2 is the ideal pairing, which reduces your chances of Alzheimer’s.

- Cost: $100 – $400

- Mitigations (for e4’s): Extend your “cognitive reserve” through varied challenges, requiring more nimble thinking and processing. This could include learning new languages, dances, topics, skills, etc. Additionally, eat low carb to improve metabolic issues, incorporate zone 2 cardio, and lean heavily on strength training.

- Liquid biopsy: This test is newer and Peter is cautiously optimistic about its potential. A liquid biopsy can detect trace amounts of cancer-cell DNA via a simple blood test. There are two primary functions, the first is to determine the cancer’s presence/absence and the second is to gain insight into the type of cancer.

- Cost: $500 – $5k, varies widely based on the range of cancer variants you’re analyzing

- Full-body MRI: ~75% of Peter’s patients get full-body MRIs, but he cautions them before getting it done. This is a useful test, but it can lead to false positives, which is the emotional cost these patients accept when getting it done.

- Cost: $500 – $3k depending on insurance coverage and the MRI facility

Exercise

Peter no longer trains for a specific event, such as cycling or swimming, but instead, he’s training for life. Specifically, the centenarian decathlon. And so shall we!

“As Centenarian Decathletes, we are no longer training for a specific event, but to become a different sort of athlete altogether: an athlete of life.”

Peter has each patient create a list of activities they’d like to do for the rest of their lives, below is an example and a starter list we could use from the book.

“Think of the Centenarian Decathlon as the ten most important physical tasks you will want to do for the rest of your life. Some of the items on the list resemble actual athletic events, while some are closer to activities of daily living, and still others might reflect your own personal interests. (p. 231)”

- Hike 1.5 miles on a hilly trail.

- Get up off the floor under your own power, using a maximum of one arm for support.

- Pick up a young child from the floor.

- Carry two five-pound bags of groceries for five blocks.

- Lift a twenty-pound suitcase into the overhead compartment of a plane.

- Balance on one leg for thirty seconds, eyes open. (Bonus points: eyes closed, fifteen seconds.)

- Have sex.

- Climb four flights of stairs in three minutes.

- Open a jar.

- Do thirty consecutive jump-rope skips.

We’ll break down exercise into its most important components: stability, cardio, and strength.

Stability

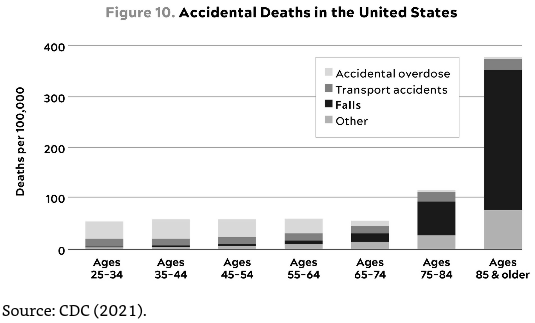

To understand why stability is so important, let’s look at an eye-popping chart for accidental deaths.

Twice a week, Peter spends an hour doing dedicated stability training, based on the principles of DNS, PRI, and other practices, with ten to fifteen minutes per day on the other days.

Sadly, he doesn’t mention many examples within Outlive for stability, but below are two starter workouts he has recommended on YouTube.

- Balance exercises: How to train lower leg variability

- How and why to practice the Barry get-up exercise

Cardio

If you’re a gym bro like me, the only cardio you’ve done is accidentally walking up a hill too fast. After realizing how critical cardio is in delaying the four horsemen I’ve radically changed my cardio routine. It’s broken up between zone 2 and VO2 max.

I’ll state up front, that Peter recommends breaking your cardio into an 80/20 split. 80% of cardio is dedicated to zone 2 and 20% is VO2 max.

Zone 2 cardio improves our [mitochondrias] ability to utilize glucose and especially fat as fuel. Our mitochondria can convert both glucose and fatty acids to energy—but while glucose can be metabolized in multiple different ways, fatty acids can be converted to energy only in the mitochondria. Typically, someone working at a lower relative intensity will be burning more fat, while at higher intensities they would rely more on glucose. The healthier and more efficient your mitochondria, the greater your ability to utilize fat, which is by far the body’s most efficient and abundant fuel source. This ability to use both fuels, fat and glucose, is called “metabolic flexibility,” and it is what we want. […] Healthy mitochondria (fostered by zone 2 cardio) help us keep this fat accumulation in check. (p. 238)

Zone 2 is more or less the same in all training models: going at a speed slow enough that one can still maintain a conversation but fast enough that the conversation might be a little strained. It translates to aerobic activity at a pace somewhere between easy and moderate. (p. 237)

You should aim for at least 3 hours a week in zone 2.

Now onto VO2 max. Simply put – 4 minutes hard, 4 minutes easy, for 5 rounds.

“The tried-and-true formula for these intervals is to go four minutes at the maximum pace you can sustain for this amount of time—not an all-out sprint, but still a very hard effort. Then ride or jog for four minutes easily, which should be enough time for your heart rate to come back down to below about one hundred beats per minute. Repeat this four to six times and cool down. (p. 249-250)”

“I push my patients to train for as high a VO2 max as possible so that they can maintain a high level of physical function as they age. Ideally, I want them to target the “elite” range for their age and sex (roughly the top 2 percent). If they achieve that level, I say good job—now let’s reach for the elite level for your sex, but two decades younger. This may seem like an extreme goal, but I like to aim high, in case you haven’t noticed. (p. 246-247)”

I recommend getting a VO2 max test once a year, so you’re able to see where you’re at and what improvements are needed.

Outlive used to have a video series of exercises housed here, but they’ve moved these to Peter’s YouTube. They’re not easy to find, so I’ve aggregated them below.

- How and why to practice breathing on the ground with hands on stomach and chest

- How and why to practice the Barry get-up exercise

- How and why to practice scapula-controlled articular rotations (CARs)

- How and why to practice this toe yoga exercise

- How and why to practice the segmental cat-cow exercise

- How and why to train balance with eyes closed

- How and why to perform a step-up exercise

Strength

Peter surprisingly didn’t provide many strength exercises throughout Outlive, but we’re lucky. He recently did an interview where he shared his top 10 exercises, which include strength.

In the book he hits home the importance of grip strength, not because big forearms are cool, but because a strong grip is indicative of overall strength.

“Training grip strength is not overly complicated. One of my favorite ways to do it is the classic farmer’s carry, where you walk for a minute or so with a loaded hex bar or a dumbbell or kettlebell in each hand. One of the standards we ask of our male patients is that they can carry half their body weight in each hand (so full body weight in total) for at least one minute, and for our female patients, we push for 75 percent of that weight. This is, obviously, a lofty goal—please don’t try to do it on your next visit to the gym. Some of our patients need as much as a year of training before they can even attempt this test. The most important tip is to keep your shoulder blades down and back, not pulled up or hunched forward. (p. 259)”

“Another way to test your grip is by dead-hanging from a pull-up bar for as long as you can. (This is not an everyday exercise; rather, it’s a once-in-a-while test set.) You grab the bar and just hang there, supporting your body weight. This is a simple but sneakily difficult exercise that also helps strengthen the critically important scapular (shoulder) stabilizer muscles. Here we like to see men hang for at least two minutes and women for at least ninety seconds at the age of forty. (We reduce the goal slightly for each decade past forty.) (p. 259-260)”

Nutrition

Peter shares three levers that one can pull to alter their weight – calorie restriction (eat less), dietary restriction (vegan, keto, etc.), and time restriction (intermittent fasting). Choose whatever works best for you and your goals.

But there is one thing that’s clear after reading Outlive, protein is the most important macronutrient. So much so, that I’ve stopped intermittent fasting to ensure I’m getting enough protein per day and so has Peter.

Protein

“How much protein do we actually need? It varies from person to person. In my patients, I typically set 1.6 g/kg/day as the minimum, which is twice the US recommended dietary allowance. The ideal amount can vary from person to person, but the data suggest that for active people with normal kidney function, one gram per pound of body weight per day (or 2.2 g/kg/day) is a good place to start—nearly triple the minimal recommendation. So if someone weighs 180 pounds, they need to consume a minimum of 130 grams of protein per day, and ideally closer to 180 grams, especially if they are trying to add muscle mass. (p. 331-332)”

Fats

Within Outlive Peter provides the ideal fat ratio.

“From our empirical observations and what I consider the most relevant literature, which is less than perfect, we try to boost monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) closer to 50–55 percent, while cutting saturated fatty acids (SFA) down to 15–20 percent and adjusting total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) to fill the gap. (p. 336)”

“I tell my patients that based on the least bad, least ambiguous data available, MUFAs are probably the fat that should make up most of our dietary fat mix, which means extra virgin olive oil and high-MUFA vegetable oils. (p. 340)”

Sleep

“Many studies have confirmed what your mother told you: We need to sleep about seven and a half to eight and a half hours a night. There is even some evidence, from studies conducted in dark caves, that our eight-ish-hour sleep cycle may be hard-wired to some extent, suggesting that this requirement is non-negotiable. (p. 354)

Try to keep your bedroom cool—around sixty-five degrees Fahrenheit seems to be optimal. (p. 371)”

Peter’s tips for sleeping

Don’t drink any alcohol, period—and if you absolutely, positively must, limit yourself to one drink before about 6 p.m. Alcohol probably impairs sleep quality more than any other factor we can control.

- Fix your wake-up time—and don’t deviate from it, even on weekends. If you need flexibility, you can vary your bedtime, but make it a priority to budget for at least eight hours in bed each night.

- Don’t obsess over your sleep, especially if you’re having problems. If you need an alarm clock, make sure it’s turned away from you so you can’t see the numbers. Clock-watching makes it harder to fall asleep.

And that’s it! Those are the practical points we can take away from Outlive, but I want to leave you with one last thing…

The reason I love Peter (and other genuine scientists) is that he changes his mind based on data. Often, when researchers become popular they turn into activists pushing their perspective on everyone… Unwilling to update their opinion. This is not science.

Peter had one of his best episodes yet where he quickly gave his opinion on a variety of topics. During this episode, he explicitly called out multiple topics he’s changed his mind on and I love it.